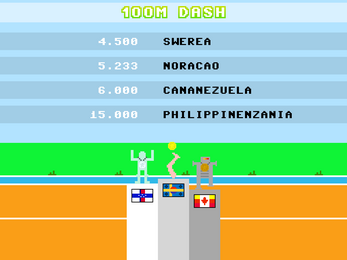

Class 10 - Classes, spritesheets, animations in Love2d

Play homework

Topics

- Animation

- Walk cycles

- Platformers

Description

We’ve previously covered the basics of Classes and of animation in Pico-8. In this week we’ll look at implementing this in Love2d to build a basic game.

Objects

In our previous work with tables we used our tables as numbered lists, but we can also store values in a different way: With strings.

function love.load()

--rect is short for rectangle

rect = {}

rect["width"] = 100

end

"width" in this case is what we call a key or a property. So the table rectangle now has the property "width" with a value of 100. We don’t need to use strings every time we want to create property. A dot (.) is the shorthand for table_name["property_name"].

function love.load()

rect = {}

-- These two are the same

rect["width"] = 100

rect.width = 100

end

Let’s add some more properties.

function love.load()

rect = {}

rect.x = 100

rect.y = 100

rect.width = 70

rect.height = 90

end

Now that we have our properties we can start drawing the rectangle.

function love.draw()

love.graphics.rectangle("line", rect.x, rect.y, rect.width, rect.height)

end

And let’s make it move!

function love.load()

rect = {}

rect.x = 100

rect.y = 100

rect.width = 70

rect.height = 90

--Add a speed property

rect.speed = 100

end

function love.update(dt)

-- Increase the value of x. Don't forget to use delta time.

rect.x = rect.x + rect.speed * dt

end

Now we have a moving rectangle again, but to show the power of tables I want to create multiple moving rectangles. For this we’re going to use a table as a list. We’ll make a list of rectangles. Move the code inside the love.load to a new function, and create a new table in love.load.

function love.load()

-- Remember: camelCasing!

listOfRectangles = {}

end

function createRect()

rect = {}

rect.x = 100

rect.y = 100

rect.width = 70

rect.height = 90

rect.speed = 100

-- Put the new rectangle in the list

table.insert(listOfRectangles, rect)

end

So now every time we call createRect, a new rectangle object will be added to our list. That’s right, a table filled with tables. Let’s make it so that whenever we press space, we call createRect. We can do this with the callback love.keypressed.

function love.keypressed(key)

-- Remember, 2 equal signs (==) for comparing!

if key == "space" then

createRect()

end

end

Whenever we press a key, LÖVE will call love.keypressed, and pass the pressed key as argument. If that key is "space", it will call createRect.

Last thing to do is to change our update and draw function. We have to iterate through our list of rectangles.

function love.update(dt)

for i,v in ipairs(listOfRectangles) do

v.x = v.x + v.speed * dt

end

end

function love.draw(dt)

for i,v in ipairs(listOfRectangles) do

love.graphics.rectangle("line", v.x, v.y, v.width, v.height)

end

end

And now when you run the game, a moving rectangle should appear every time you press space.

One more time?

That was a lot of code in a rather short tutorial. I can imagine it can be quite confusing so let’s go through the whole code one more time:

In love.load we created a table called listOfRectangles.

When we press space, LÖVE calls love.keypressed, and inside that function we check if the pressed key is "space". If so, we call the function createRect.

In createRect we create a new table. We give this table properties, like x and y, and we store this new table inside our list listOfRectangles.

In love.update and love.draw we iterate through this list of rectangles, to update and draw each rectangle.

Functions in objects

An object can also have functions. You create a function for an object like this:

tableName.functionName = function ()

end

-- Or the more common way

function tableName.functionName()

end

Summary

We can store values in tables not only with numbers but also with strings. We call these type of tables objects. Having objects saves us from creating a lot of variables.

Animation

Frames

Let’s make an animated image.

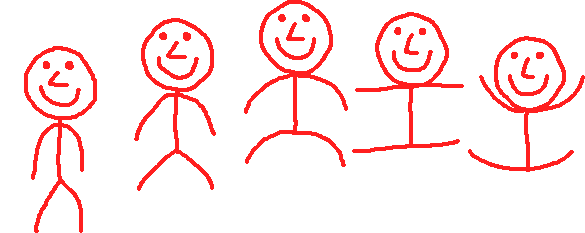

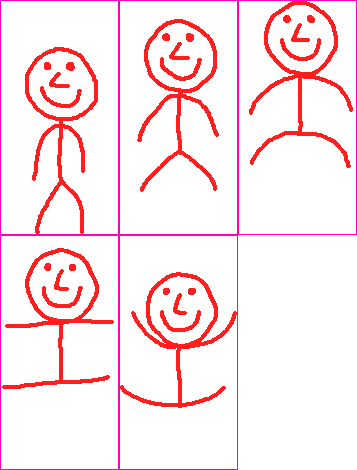

First, you’ll need some images:

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

You can also download them as a zip here

Load the images and put them in a table.

function love.load()

frames = {}

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newImage("jump1.png"))

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newImage("jump2.png"))

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newImage("jump3.png"))

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newImage("jump4.png"))

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newImage("jump5.png"))

end

Hold on, we can do this much more efficiently.

function love.load()

frames = {}

for i=1,5 do

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newImage("jump" .. i .. ".png"))

end

end

That’s better! Now we need to create an animation. How will we do that?

A for-loop?

Nope. A for-loop would let us draw all the frames at the same time, but we want to draw a different frame every second. We need a variable that increases by 1 every second. Well that’s easy!

function love.load()

frames = {}

for i=1,5 do

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newImage("jump" .. i .. ".png"))

end

--I use a long name to avoid confusion with the variable named frames

currentFrame = 1

end

function love.update(dt)

currentFrame = currentFrame + dt

end

Now we have the variable currentFrame which increases by 1 every second, let’s use this variable to draw the frames.

function love.draw()

love.graphics.draw(frames[currentFrame])

end

If you run the game you’ll get an error: bad argument #1 to ‘draw’ (Drawable expected, got nil)

This is because our variable currentFrame has decimals. After the first update currentFrame is something like 1.016, and while our table has something on position 1 and 2, there is nothing on position 1.016.

To solve this we round the number down with math.floor. So 1.016 will become 1.

function love.draw()

love.graphics.draw(frames[math.floor(currentFrame)])

end

Run the game and you’ll see that our animation works, but you’ll eventually get an error. This is because currentFrame became higher than (or equal to) 6. And we only have 5 frames. To solve this, we reset currentFrame if it gets higher than (or equal to) 6. And while we’re at it, let’s speed up our animation.

function love.update(dt)

currentFrame = currentFrame + 10 * dt

if currentFrame >= 6 then

currentFrame = 1

end

end

Look at him go!

Quads

So this works, but it’s not very efficient. With large animations we’re going to need a lot of images. What if we put all the frames into 1 image, and then draw part of the image. We can do this with quads.

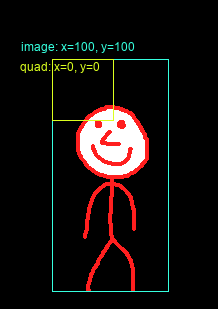

First, download this image:

We’ll remake the function love.load (you can keep love.update and love.draw the way it is).

function love.load()

image = love.graphics.newImage("jump.png")

end

Imagine quads like a rectangle that we cut out of our image. We tell the game “We want this part of the image”. We’re going to make a quad of the first frame. You can make a quad with love.graphics.newQuad (wiki).

The first arguments are the x and y position of our quad. Well since we want the first frame we take the upper-left corner of our image, so 0,0.

function love.load()

image = love.graphics.newImage("jump.png")

frames = {}

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(0, 0))

end

Again, quads are like cutting a piece of paper. Where we will eventually draw our image is not relevant to the quad.

Next 2 arguments are the width and height of our quad. The width of a frame in our image is 117 and the height is 233. The last 2 arguments are the width and height of the full image. We can get these with image:getWidth() and image:getHeight().

function love.load()

image = love.graphics.newImage("jump.png")

frames = {}

local frame_width = 117

local frame_height = 233

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(0, 0, frame_width, frame_height, image:getWidth(), image:getHeight()))

currentFrame = 1

end

Now let’s test our quad by drawing it. You draw a quad by passing it as second argument in love.graphics.draw.

function love.draw()

love.graphics.draw(image, frames[1], 100, 100)

end

As you can see it’s drawing our first frame. Great, now let’s make the second quad.

To draw the second frame all we need to do is move the rectangle to the right. Since each frame has a width of 117, all we need to do is move our x to the right with 117.

function love.load()

image = love.graphics.newImage("jump.png")

frames = {}

local frame_width = 117

local frame_height = 233

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(0, 0, frame_width, frame_height, image:getWidth(), image:getHeight()))

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(frame_width, 0, frame_width, frame_height, image:getWidth(), image:getHeight()))

end

And we can do the same for the 3rd quad.

Wait, are we repeating the same action? Don’t we have something for that? For-loops! Also, we can prevent calling :getWidth and :getHeight multiple times by storing the values in a variable.

function love.load()

image = love.graphics.newImage("jump.png")

local width = image:getWidth()

local height = image:getHeight()

frames = {}

local frame_width = 117

local frame_height = 233

for i=0,4 do

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(i * frame_width, 0, frame_width, frame_height, width, height))

end

currentFrame = 1

end

Notice how we start our for-loop on 0 and end it on 4, instead of 1 to 5. This is because our first quad is on position 0, and 0 * 177 equals 0.

Now all that is left to do is use currentFrame for the quad we want to draw.

function love.draw()

love.graphics.draw(image, frames[math.floor(currentFrame)], 100, 100)

end

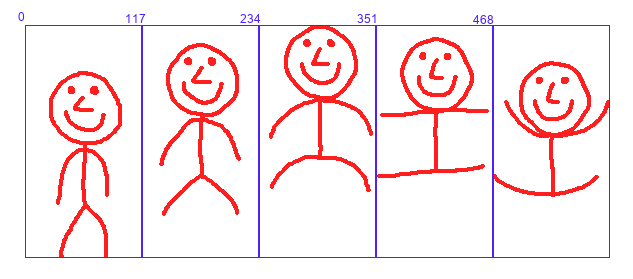

Multiple rows

So we can now turn a row of frames into an animation, but what if we have multiple rows?

Easy, we just have to repeat the same thing with a different y value.

function love.load()

image = love.graphics.newImage("jump_2.png")

local width = image:getWidth()

local height = image:getHeight()

frames = {}

local frame_width = 117

local frame_height = 233

for i=0,2 do

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(i * frame_width, 0, frame_width, frame_height, width, height))

end

for i=0,1 do

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(i * frame_width, frame_height, frame_width, frame_height, width, height))

end

currentFrame = 1

end

But wait, there it is again: Repetition! And what do we do when we see repetition? We use a for-loop.

So what, like, a for-loop inside a for-loop?

Exactly! We’re going to have to make a few changes though.

function love.load()

image = love.graphics.newImage("jump_2.png")

local width = image:getWidth()

local height = image:getHeight()

frames = {}

local frame_width = 117

local frame_height = 233

for i=0,1 do

--I changed i to j in the inner for-loop

for j=0,2 do

--Meaning you also need to change it here

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(j * frame_width, i * frame_height, frame_width, frame_height, width, height))

end

end

currentFrame = 1

end

So in the first iteration of the outer for-loop, i equals 0, and j equals 0, then 1 and finally 2. In the second iteration, i equals 1, and j again equals 0, then 1 and finally 2.

You might notice that we have an extra, empty quad. This isn’t really a big deal since we only draw the first 5 quads, but we can do something like this to prevent it

maxFrames = 5

for i=0,1 do

for j=0,2 do

table.insert(frames, love.graphics.newQuad(j * frame_width, i * frame_height, frame_width, frame_height, width, height))

if #frames == maxFrames then

break

end

end

print("I don't break!")

end

With break we can end a for-loop. This will prevent it from adding that last quad.

Note how “I don’t break” gets printed. This is because break only breaks the loop you use it in, the outer loop still continues. It could be fixed by adding the same if-statement in our outer-loop, but in our case it doesn’t matter since the loop at that point is already on its last iteration.

Bleeding

When rotating and/or scaling an image while using quads, an effect can appear called bleeding. What happens is that part of the image outside of the quad gets drawn.

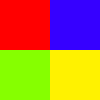

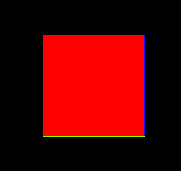

So if this was our spritesheet:

Our first frame could end up like this:

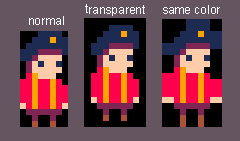

It’s kind of technical why this happens, but the fact is that it does happen. Luckily, we can solve this issue by adding a 1 pixel border around our frame. Either of the same color as the actually border, or with transparency.

And then we don’t include that border inside the quad.

I added a border to our jumping character. Instead of transparent I made it purple so that we can see if we’re not accidentally drawing part of the border.

Let’s do this step by step.

First, we do not want the first pixel to be drawn, so our quad starts at 1 (instead of 0).

newQuad(1, 1, frame_width, frame_height, width, height)

Okay so this works for the first frame, but what part of the next frame do we want to draw? Simply add the frame width/height?

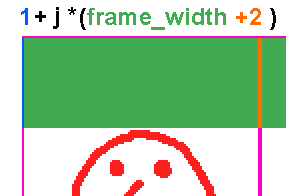

newQuad(1 + j * frame_width, 1 + i * frame_height, frame_width, frame_height, width, height)

Almost. We’re missing something.

The blue line is our quad. As you can see, the quad is 2 pixels to the left of where it’s supposed to be. So let’s add 2 to how much we move each iteration.

newQuad(1 + j * (frame_width + 2), 1 + i * (frame_height + 2), frame_width, frame_height, width, height)

And now our quads are in the correct position. Here’s an image visualizing how we position the quad. So we add 1, then add frame_width + 2, multiplied by i. This way we position the quad correctly for each frame.

Code homework

For homework, you will be working on a platformer game.

Build a basic level that you can demonstrate and allow playtesting next week. You should have a player, keyboard control, animation, an ability to jump, fall, etc.

Credits

- Copyright (c) 2022 Sheepolution

- Pong 0: MIT Open Courseware Colton Ogden & David J. Malan 2018

- Frogger screenshot, Konami, Sega (Apple II)

- Paperboy illustration, robinstam