A little over a year ago I began a regular code sketching practice. Code sketching is the process of working in code to make visual or multimedia artworks with an emphasis on rapid prototyping (Note: this is my own informal definition). Code sketching is the computational equivalent to analog sketching with pen on the notebook page. The Processing development environment even calls itself a flexible software sketchbook and it uses the term sketches to indicate a Processing project. The directory holding all of these sketches is called the sketchbook.

When I began code sketching I was inspired by other artists working in code who create daily code sketches, most prominently Zach Lieberman. In addition to Zach I’ve since also learned about the work of Beeple, Saskia Freeke, Reza Ali and Simon Alexander-Adams, among many others.

Everyday code sketches site in 2019, with questionable design choices

My own code sketching audiovisual work is online here.

The actual code for these code sketches can be found in this GitHub repository.

Zach wrote a great post in 2016 and another in 2017 where he lays out his motivations, process, goals and outcomes.

Two of his goals stick out to me:

- Keep sketches really simple

- Prioritize iteration over novelty — how can I push an old sketch to be new?

Zach does a great job of showing his work and describing his practice in this 2017 talk he gave for the American Institute for Graphic Arts. What I like about his process is the emphasis on iteration, using yesterday’s code sketch potentially as the basis for today’s. What code can be copied, then modified to move forward into new and surprising territory? Part of the goal of his code sketching is to engage with an audience. He makes daily posts of his work as video on Instagram. A significant number of Zach’s code sketches find their way into commercial projects.

My goals

My own goals and practice tweak Zach’s formula. I would say my own initial goals were:

- Work quickly so I don’t get bogged down and overwhelmed by longterm projects, which could contribute to me feeling down on myself.

- Enjoy the adrenaline rush and excitement and accomplishment that comes when you finish a mini project, no matter how small.

- Learn and practice new techniques even if I’m not sure where I’ll use them again.

- Challenge myself to make things that I don’t necessarily know how to do.

- Go quickly from conception to prototype work, a challenge when working in code.

- Don’t be limited to creating generative moving image works. It’s okay to try out technical things, build tools, or make mini apps and websites.

- The web is a platform for art, reading, tools, space, etc. so works will live as pages on a website, available from a phone or desktop, easily shared.

I didn’t write these rules before I began. I just had them loosely in mind and let myself begin, and to see where it went. Now that it’s been a year, I’m looking at the work I made and reflecting on the works and my process.

I’m an artist and educator teaching programming in the arts, new media and math/computer science. I’m also really interested in toolbuilding, building my own or tweaking other’s tools that can be used in the process of art creation. For this reason, some of my code sketching doesn’t look very sketch-like: it can look more like prototyping of tools or techniques. In this way, I considered the rapid prototyping of a tool as another form of sketching with code. Unlike how I think of others engaged in code sketching, a good number of my created projects do not necessarily involve creating generative moving images, though more than half do. And in fact, the goal of at least a couple of my sketches was the ability to save user-created work as various data files. I don’t consider this a failure or mistake. I enjoyed the challenge of attempting to build these tools, and they were useful prototypes that I can refer to and borrow code snippets from later. Additionally, I have a broad background including in experimental music composition, so I also created (though sometimes sampled) audio tracks to accompany many of these sketches or drive its direction.

Working with the browser brings its own rewards and challenges, which I’ll detail below, including the challenge of working with sound.

Tools I used

On my code sketching page I wrote:

These are meant to be sketching with code. I’m using html, css, js and the p5js and jQuery libraries.

For the most part, I kept to only these tools, not just because I was already working in them and felt comfortable, but because there was a lot I could do with these and much more to learn and I enjoyed working with the web browser as my canvas.

HTML and CSS as code sketching tools

For the first few weeks, I challenged myself to create experimental audiovisual works with HTML and CSS, the basic domain language building blocks of the web. Much like artist Rafael Rozendaal’s art websites, I used CSS animations techniques and keyframes to move colors, shapes and patterns. This isn’t a widely discussed practice in creative coding. There’s more of a dialogue on languages like Processing, OpenFrameworks, Shader coding, for example. But I found the quick start-up process of working with CSS animation really nice. And you don’t need any special software or library to make or view the work, just a text editor and a web browser.

Overall, just by adding a few lines of CSS, I could tweak numbers and colors and make big changes to my works, which means it’s easy to see results. Honestly, I could have spent the whole year just working this way with CSS. And perhaps I should have! Again, see Rafael’s websites for excellent examples of work made this way. I think one goal in the year ahead will be to go back and work more on CSS animation artworks.

Advantages of working with CSS to do creative coding:

- Its regularity in terms of how it’s written and how it works. (Element Selectors)

- It’s not a special add-on library to the web, it IS the web. It just works.

- Lots of resources to learn things online. It’s been in use 2 decades, with progressive add-ons to this domain-specific language. All info is usually found in an easy web search.

- Its capability for rapid prototying/making. I had my code in one window and my web browser open next to it. I’d make an edit to my code and save, then reload the page in the web browser to see the change. With a simple plugin in Atom or other code editor you can even have your browser automatically self-reload.

- Its output lives on a website, which means it’s accessible on everything with a web browser (phone, laptop, etc.

- Newer capabilities like CSS grid and Flexbox make it easier to place things on a page.

- It works with Javascript, which means that you can make your CSS interactive with the addition of JS code.

- Nothing proprietary here. This is as open source and free as you can get.

Complaints about the web as a platform

Now that I’ve said what I like, allow me to complain a bit. There are a few serious disadvantages to using the web as a platform or space for presenting artwork and/or code sketching.

- How to place things on the page is fairly unintuitive, though it’s gotten a bit better with flexbox and css grid.

- There are some occasional but serious consistency issues between the browsers for newer features, which requires visiting Can I Use ___? to look up how or whether a particular browser implements that feature.

- When something doesn’t work how you expect, it can be a pain to debug. There aren’t error messages. The main way is to open your browser’s Inspector and look at different elements’ assigned CSS and click checkboxes to turn things on and off.

The most significant issue I dealt with is how differently my sketches could appear or function on different web browsers. Accessing the camera to make generative video work later in the year worked fine when I was coding, but ceases to work in the browser when placed online for others because of the new browser restrictions placed on domains lke my own that don’t use https. I also had to get used to how things would sometimes look different in the various browsers and the various implementations/versions of them. I primarily use Firefox, and so sometimes things look funky in Safari or Chrome since my primary audience was myself! If was creating production code I’d want to build more robustly, but I was code sketching here; I didn’t want to get bogged down into the nitty gritty issues of dealing with the DOM, but unfortunately, there I was.

Additionally, I said before that almost everything has a browser, including our phones, but coding projects meant to be seen on a phone is an extra level of challenge. Sometimes I added extra CSS media queries or edited my work to make sure it was mobile-responsive, but most of the time I left that off, again so I wouldn’t get bogged down while sketching in code.

By far the most annoying thing I dealt with was that mid-year in 2019 web browsers changed their implementation of auto-playing sound. One could no longer trigger a backing audio track or generative sounds to play unless you code in for the user to trigger an event like pressing a button. I understand this is to prevent auto-playing advertisements, but it still messed my art up! I had all these self-playing audiovisual generative pieces where the visuals moved or responded to the audio track. They stopped working! I ended up starting to code in button presses or mouse button prompts, but the audio on a bunch of my earlier code sketches would have to be changed, and since they were sketches I just didn’t feel like going back to them.

I think this is why Zach says that his process is to code, then do screen capture and post to Instagram. And I noticed other code sketchers with the same process. It’s true it’s a good location to get eyes and engage with other folks. But secondarily, they don’t have to worry about code working across computers, or to have to respond to changing languages and implementations. The work is viewable as video on a proprietary, ubiquitous website/app, Instagram, as long as that platform is maintained and there’s an audience.

Generative CSS works with jQuery and plain Javascript as creative coding tools

Pretty quickly I started working with Javascript to modify the CSS. I did this because of Javascript’s use as a tool to modify HTML or CSS based on specific events, or to be able to use random number generators. This let me build more complex behaviors of things that changed over time on my webpage such as changing colors, sizes, locations.

The first add-on library I worked with was the jQuery javascript library. In this day and age, jQuery has fallen out of favor among professional programmers. Without getting too much into the technical details, this Javascript library makes it really easy to select any HTML elements (text, images, parts of your page) and apply changes to their style based on events that happen in the browser (when you click a button…when the page loads…after a certain amount of time…etc). This long-lived library is so useful that a lot of its ideas were integrated back into the main Javascript language, and many professional developers use tinier libraries to add back in smaller subsections of this library for their own use. But I’m not a professional developer and I think jQuery is still a useful, easy and fun-to-use tool, so at least for the first part of the year I used it. Over time I learned tricks in vanilla Javascript to replicate the ease-of-use of jQuery.

At first I did very simple code sketches, with not many lines of code. My earlier code sketches involved a plain minimal HTML webpage and a few lines of CSS. As mentioned, I was playing with CSS animation, using it to move and color things. I was (still am) a big fan of creating gradients and playing with moving grids, so I started there for many earlier code sketches.

So for my first few projects I made use of 'transform': 'rotate('+rot+'deg)' to rotate things and keyframes to move things around over time. These were the tools in my toolbelt.

View the full Project 5 page.

Most of the code comes down to this:

HTML:

<p>...</p>

What it says: Create an ellipses.

CSS:

p {

background: linear-gradient(to top right, lime, white);

font-size: 25em;

color: grey;

width: 40%;

display: block;

}

What it says: Grab the paragraph, give it a background color gradient from lime to white. The text is grey, size 25.

jQuery/Javascript:

setInterval(function(){

$('p').css ({

'transform': 'rotate('+rot+'deg)',

'width': rot,

'height': rot

});

rot+=10;

if (rot>5000){rot=0;}

}, 100)

What it says: Set a function into motion so that every 100 milliseconds the ellipses paragraph block gets rotated an additional 10 degrees clockwise. Additionally, increase the height and width by 10 pixels each time so it’s a constantly growing square. If it hits 5000 pixels in width/height then reset it to size zero again and it will continue to grow again.

This is not particularly difficult or brilliant breathtaking code but it produces a simple beautiful result. Mini code sketches like this are what started me on my path.

Code sketching with p5.js

Later I switched to spending more time with p5.js (abbreviated p5) instead of jQuery,because I was teaching it in my Programming For Visual Artists class in Purchase that spring. I’m comfortable with it, and I like being part of the community of those that work with it and organize in it. The other reason I started working more with p5 is because I was making interactive works with less emphasis on generative CSS techniques. I needed more advanced building tools, and p5.js shares history and ethos with Processing, so it’s a natural way for me to work.

Some of the first sketches I made with p5 diverged a lot from the earlier CSS experiments. My sketches 16 and 17 are dice-rolling apps. Around that time I was developing lesson plans and wanted to show randomness. There isn’t an ability to get random numbers in CSS alone without Javascript or CSS pre-processers. From my dice roller sketches I took my random number selection and quickly iterated on it, having the page play a video file of a mouth and select a random sound (my voice) to play to accompany it, for example.

Building Microtools

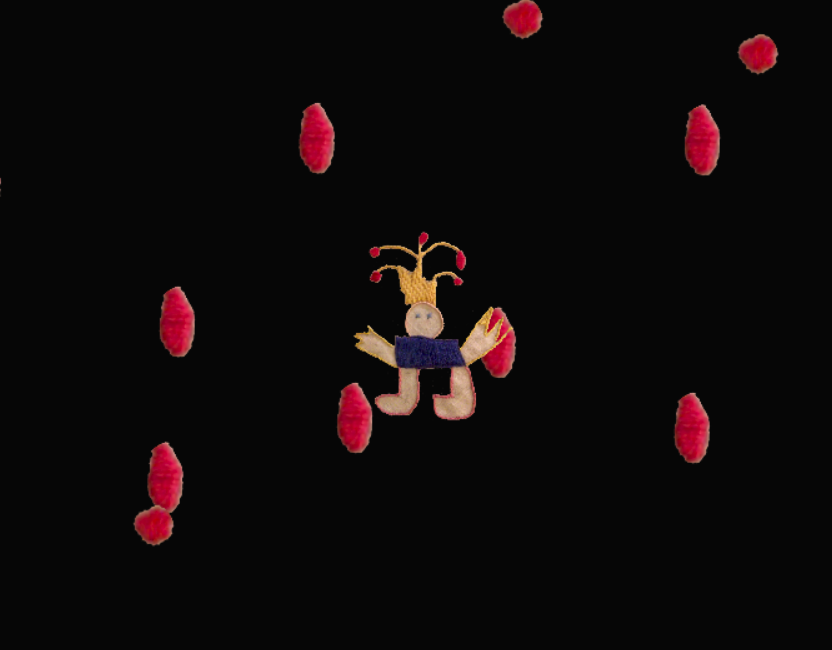

I started building out other tools and using my in-progress framework that I call p5.flatgame, a tool to build flatgames using the p5 library. A flatgame is a 2d game world where a single character walks around and explores the world. There is no interaction, score, death, or even levels. Creating a flatgame is an experiment in miniature scene-building. The emphasis is on exploration and sometimes telling a narrative story. I’ll write more on flatgames in a future post.

a flatgame made using a photo of an embroidery

I also built simple art-builders. For example, I think 24 were scans of doodles on a pad, that turned into a weird mini art-stamper picture maker. I used this to build the art for a flatgame, 26, a few days later, which also features my voice and a self-portrait as the walking character.

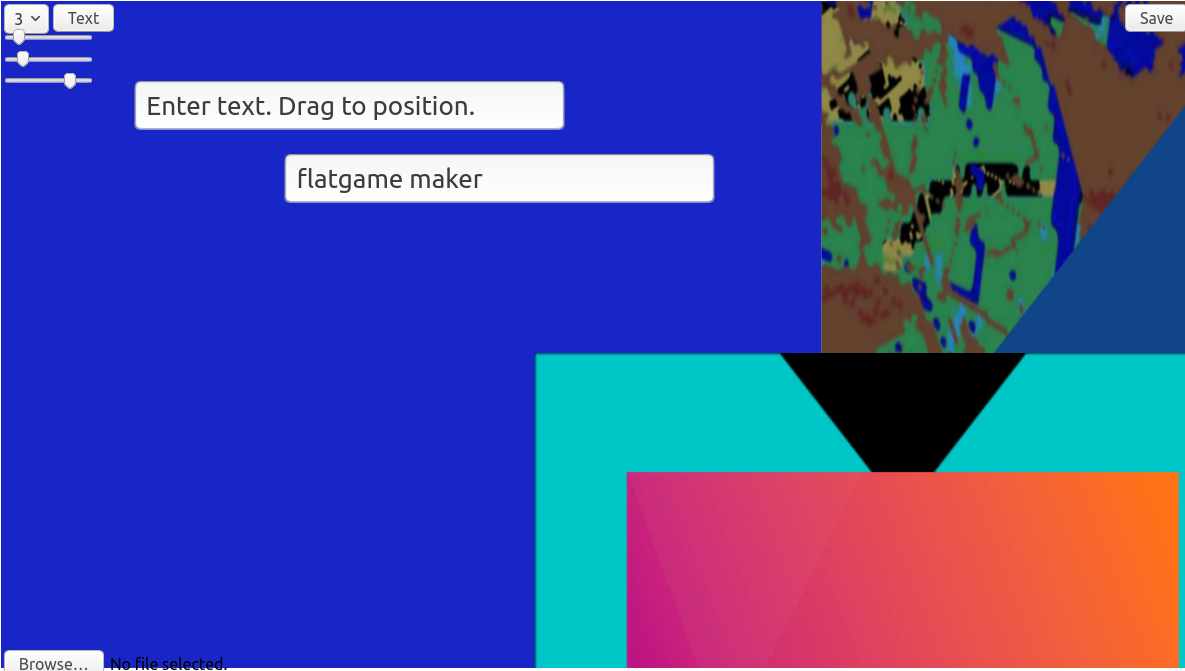

This is a very sketchy prototype of an in-progress javascript-based flatgame-maker

After that I worked on iterative prototypes of a flatgame-maker that I created during my artist-in-residency at Signal Culture, and presented in a workshop during the Processing Community Day LA 2019 and turned into a collaborative workshop code sketch in my workshop Games For All! - Flatgames with p5.play.

a generated collaboratively-built flatgame

This sketch above was created by a collaborative group of 30+ individuals made up of adults and kids at Processing Community Day Los Angeles in my workshop.

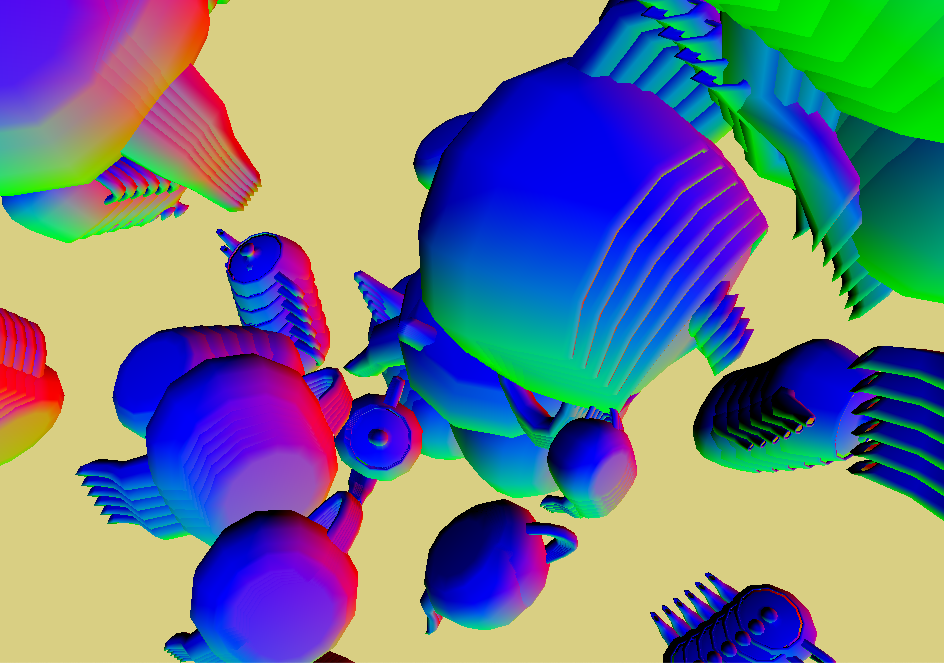

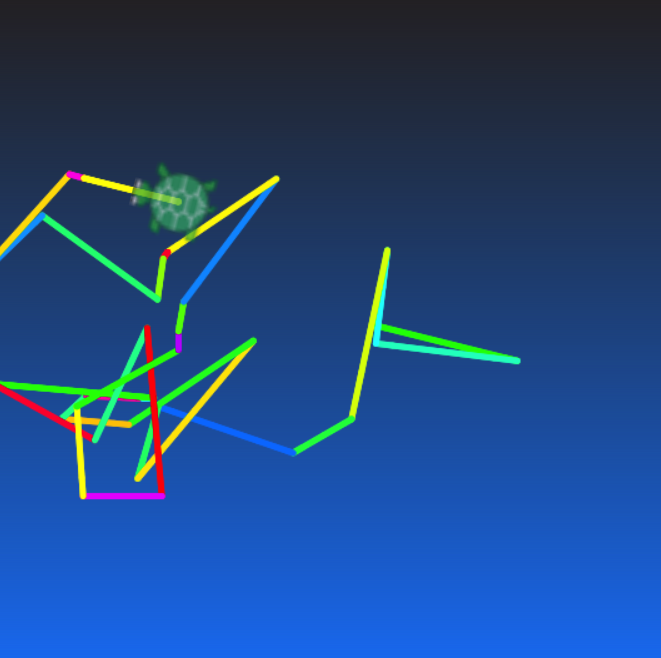

Generative 3d art with WEBGL in p5.js

I took a break from toolbuilding for a while and turned to what I’ll call bread-and-better code sketching, i.e. generative visuals.

this glitching-out code sketch responds to an audio track, pulsating dramatically based on volume

Very quickly I turned to working in 3d using WEBGL with p5.js. Working this way there’s quite a bit less built-in functionality than using the Unity3D game engine for example. You build up from simple geometric shapes, or import 3d objects, or turn 2d primitives into 3d shapes.

Some of my tricks I used: map position to volume of audio, so that the audio drives the motion and scale. Use map in p5.js so that as I move across the page I am rotating objects.

It’s easy to work with some simple glitching aesthetics in WEBGL with p5.js. Essentially, just don’t redraw the background, and then every frame builds on top of the previous one in 3d space.

I used text in 3d as well, and dropped in google fonts.

A lot of these works involved audio, my own or others. They almost became background concert visuals.

Revisiting an idea I had in Unity a year or two earlier to build a generative floor from sampled images.

In the summer I traveled to a few countries. I visited Taiwan and built some flatgame-style works, some that can be played with the mouse.

I iterated at first by changing just the assets, and created a generative 2d self-playing cyberpunk-ish glitch story that started to become its own piece. I got excited about this way of working, creating zero-player pieces.

I also worked on creating interactive works, building out a head using primitive 3d shapes and mapping and texture-wrapping (which doesn’t work well yet in p5).

this is a talking avatar, that moves its lips based on microphone input

I made a generative art-making tool called PaintMaster 5054. I ended up using this tool a ton to make background graphics or skins for lots of other works, and even submitted some of the generated pieces to exhibit calls. This used a combination of predrawn sketches from me (created in drawing software on my ipad), and re-fed and manipulated with filters and rotation in my program. This process of using a combination of my own hand drawn digital sketches mixed with some filtering or other generative techniques produces results that I really like and feel more natural to me than working completely with digital sources and primitive shapes. It retains some of the zinester quality that’s a big part of my own background interests and DIY art community. It’s also what makes my works feel more like me and contains my own signature hand in them. I’ll do more of this.

For example my Speculative Baldness Simulator used assets taken from PaintMaster.

Sound

This used images from the PaintMaster code sketch to accompany generative audio

Around this time I started getting back into the Disquiet Junto community, a weekly web-based sound art and music making community of practice, that lives in several online fora and via the weekly emails of musician/writer Marc Weidenbaum. Every Thursday Marc sends out an email containing instructions or constraints to make a sound work under a particular weekly theme. He asks for results to be recorded and put online by the following Monday evening. After reading about Brian Eno’s process for creating Music For Airports, I created a few extremely minimal sample-playing sites, almost ambient playing FM3 Buddha Machines.

I play a genre of oldskool games called Roguelikes, a category of games that feature top-down generated worlds (different every time). They feature turn-by-turn play instead of rapid realtime arcade action, along with gridded worlds, and lots of puzzle solving. Roguelikes as a genre are so old that many were originally created in ASCII text. The genre is notorious for being hard to play and hard to create games within, and that most people that play them also try to build them. One of the advantages of making a roguelike is that you will make a game that surprises you. They’re just chock full of randomization to generate enemies, maps, puzzles, levels, etc. The disadvantage is that just to get a working mini game takes tons of code. I’ll probably write another post somewhere else about coding roguelikes with no libraries on the web, but suffice it to say, just to get started, I made a goal of getting a simple grid world up on the screen and the ability to move around it.

I did a few roguelike experiments, making glitchy little things, around the time I visited the Roguelike Celebration conference. Later I added in the ability to attack enemies. I also played around with graphics. I tried to make new aesthetic choices based on the oldskool aesthetics of many roguelikes.

I did some mini GUI-toolbuilding experiments, creating a minimal way to build buttons in the browser and to add actions to them.

I spent November doing a few things for National Novel Generating Month, which I wrote about previously, but again I consider them to also be sketching with code.

I also built a scanner-camera. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work on my personal website right now because you can’t access the camera without https security, but I’ve put a version hosted on glitch.com that you can use in the browser.

I also spent time goal-setting near the end of the year, and would you be surprised, I built a goal-sheet-maker tool, inspired by artist Daniel Canogar goal organization lists.

Generated zines and poster-making tools

In the last week I’ve been put a dozen hours into working on an interactive generative Zine-making software, and an inter-related generative poster/flyer designer that I think I will build into more substantial projects.

I have lots of generated zine and poster images, but I’ll save displaying and showing this for a future post.

And that takes me to today. I made just under 90 sketches in a little over a year, about a code sketch every 4 days. That’s not bad, particularly since although some only took 30 minutes many of them I kept working on 5 or 10 hours.

Going forward

Now that the year has gone by, I feel good about this accumulation of work and tests and experiments. I’m ready to try some other things. I want to spend time working in Unity. I feel like I’ve hit the limit of what I can do with 3d worldbuilding in p5. I’ve made some projects in Unity and am teaching it, so now it’s time to go deeper. This has the advantage that it’s a much more robust tool for worldbuilding, but its serious drawbacks are that it’s not open source, it takes more robust hardware and larger screen real estate. I can’t imagine it will feel great using Unity on my daily driver small Ubuntu laptop even though it’s a powerful machine. It’s also not great for sharing to the web as a website. It can render to WEBGL, which can work for some projects. I can also screengrab, which is how Zach Lieberman’s explains his process. Screencapture -> ffmpeg to make smaller -> send to phone –> post to instagram. This is a klunky process! Especially since I’m primarily coding running on an Ubuntu-based Linux computer. That’s no knock on the computer, which I love, but on the inability to use Apple’s proprietary Airdrop. I’ve used other methods instead. I will probably try out some version of this approach and pause on my website posts and switch to sharing more on Instagram. As opposed to websites, Unity projects can be sprawling files and folders. I’m worried it will be harder to share and iterate off of earlier work. But I’ll try my best. And I have a feeling I’ll do more p5js and javascript code sketching. I do really love these tools, and it lets me easily make tools to share with others on the web.

I also intend to try more of the quick iterative sketching stressed by Zach. I’ll take the previous work, make some hack or change, then see where it takes me. In this way, maybe I can take the comparative unwieldiness of Unity and turn it into a more intuitive and rapid tool for myself, or use tools like Fernando Ramallo’s Doodle Studio 95. By the end of the year of coding, I was building my own iterative tools for further art generation, so my own code sketches bootstrapped later sketches, and I can start to build up combinations of them, like my own lego-tool collection.

My organization of everything

My entire code sketching sat in a folder called everyday. Each sketch was essentially a website in its own numbered folder. So I have a folder 1, then 2, then 3, etc. I almost always began by making a new folder mkdir 4 and then copying the previous code sketch’s folder contents into the new one. cp 3/* 4/ would copy my index.html style.css sketch.js over.

I hid some commented fleeting thoughts and mini poems at the top of my index’s in <!-- --> tags or at the top of my javascript sketches in comments.

My everyday site was organized this way:

everyday/

--------index.html

--------lib/

-----------p5.js

-----------p5.sound.js

-----------jquery.js

---------1/

-----------index.html

-----------sketch.js

-----------style.css

---------2/

---------3/

...etc....

Code sketching Recommendations

After reflecting on my year 1 of code sketching these are some tips I’ve thought of. These are not just for others but also to capture them in one place to remind myself of them.

- It’s okay to miss some days! I took days or weeks off, but I always came back to it because I really enjoyed it. Only do this if it sounds like fun and not work!

- Follow Zach’s advice: Iterate on a previous day’s work and make smaller code changes that have larger visual results.

- But also explore new territory. Don’t crank out what you’ve already been doing.

- It’s difficult to combine working with both audio and video, especially for the web, so consider how important that is to you.

- It can be a pain to make work to be seen on both desktop and mobile, so consider how you want your work to be seen and what shortcuts, starter code or approaches you can take based on that. For example, consider Zach’s approach to do screencapture and transfer to phone to post to Instagram.

- Consider your audience. I was my own audience primarily at first because I didn’t want to make sure the work was good enough to share. Now that I’m quite happy with a lot of the work I’m starting to want to share the work more publicly by posting regularly to Instagram for example, and posting here. So that means I now need to make the work ‘document well’.

- Consider how and where you’ll work on the code sketching. In the morning? At night? (My best time was before bed, but that’s not for everyone).

- Make it easy to get started just jumping into code sketching. What’s your ideal coding environment? I mean: what’s the browser, text editor, keyboard, etc that will make you feel comfortable?

- Consider your platform, if any. Zach and many others just publish to Instagram. I’m pretty anti-corporate platform, so I compromised and published to Instagram somewhat, but I also wanted to host my own site I had more control over. I used GitHub and published to GitHub pages so that my work was collected and published to an index page on my website. It’s also on my own computer and backed up, and can easily deploy to another website if GitHub ever goes down. If you’re coding in javascript you may want to just use a site like Glitch. This would be particularly useful since you can literally click remix on a previous day’s website-project and it will spin up a copy of the entire page that you can then start to edit and change and publish the new code sketch page instantly. If you go that route, I still recommend making a launcher/index page somewhere, perhaps linked off your own website that links to all your daily code sketches.

And that’s my 2019 code sketching wrapped.

Here’s some links to others’ work to see their work and learn more about their process. My own code sketches are here. My code is in this GitHub repository.

If you start a code sketching practice and keep with it, reach out and let me know. I’d love to take a look.

Links

Here are some links you may want to check out for inspiration or just to see what other people have done.

Saskia Freeze wrote on her Daily Art. She is primarily working with Processing.

Zach Lieberman’s posts in 2016 and 2017. He uses OpenFrameworks, the language he founded.

An interview with Beeple, Creativity is Hustle. He does his daily sketching with Cinema4D, not code as far as I can tell.

Simon Alexander-Adams wrote the post Developing a Daily Practice: Generative Art in Touch Designer, that looks interesting as well.

I’m curious to learn about anyone maintaining a sound ‘sketch’ or sound demo practice, particularly with a tool like Max or Pure Data/PD. This year I started playing a lot with my modular synth and have been thinking about ways to document / share that.