What is Version Control?

Version Control is the practice of saving copies or snapshots of your code at each significant stage as you work on a project. Like a meta-undo, version control lets you move forward and backward in time to get to different versions of your code across a project’s files. Without version control software, you might take a DIY approach by copying a project’s entire directory and naming it with the date. But what if you want to make multiple copies with slightly different versions and you want to use parts of each of these versions? What if you want to share and work simultaneously on a project with partners? How can multiple people collaborate together over time? Version control software lets you do this.

Git is local version control software that you run on your own computer. It lets you track changes to your files incrementally over time. Each project has its own git files. GitHub is a software company as well as the name for the website where you can post your projects you are tracking with git. You take copies of your git-tracked programs and push them to a remote GitHub server. You should know there are alternative websites and repository managers including GitLab, Bitbucket, SourceForge and others. In this article, I’ll only be covering GitHub.

I also recommend Version Control By Example, an affordable and easy-to-read book, along with free online version.

Why Use Git and GitHub?

- track changes (a.k.a. version control = undo or go back to earlier version of your program if you made a mistake)

- to save your content and all of its changes on a remote server

- to share your code with others

Version Control models

- centralized - one central server. each person checks out and merges changes to a main server. only one person can “check out” the code at a time.

- distributed - each person has a local repository. when they make changes, they “check in” with the main online copy and reconcile the two together. (GitHub is this style)

Goals of Git

- It’s fast - add to your team and code base quickly

- it’s distributed

- each commit has a corresponding hash (meaning every single change is tracked)

- everyone working on the code has a local copy of the history of the program

- If you fork (aka copy) someone else’s code/program, you pull it onto your computer so that you can edit the code. Afterwards, you can push it to your own online repository (aka repo) or you can do a pull request to the original code and that person will look at your code and decide to integrate the two together (or not).

Installation

On a Mac, you get Git when you install XCode or the XCode Command Line Tools.

Set up GitHub for your machine

You should only need to do this section once!

Set the default name for git to use when you make a commit.

git config --global user.name "Your name Here"

Set up your email connection

git config --global user.email "your_email@example.com"

Your first tracked file

- Create a project folder

- use a text editor and save a text file called hello_world.txt to your folder

- tell git to track changes

Use git init to initialize tracking your project folder aka your local repository.

Now let’s add your files(s)

git add hello_world.txt

You can always check your repository status with

git status

Your file is now being tracked by git. Let’s tell git to commit the file.

git commit -m "First commit. Added hello world to repository."

Make sure you include the -m flag. Without it, your Terminal application will likely launch Vim, a text editor, and it’s not particularly beginner-friendly.

What did we just do? How is this different than saving a file?

- When we add a new file, we tell Git to add the file to the repository to be tracked

- We say

git add filenameto stage a file. When we stage an existing file, we are telling Git to track the current state of the file. - A commit saves changes made to a file, not the file as a whole. The commit will have a ‘hash’ so we can track which changes were committed when and by whom

STANDARD WORKFLOW with Git

We will work in our IDE and each time we get to a good stopping point/save point, we will save our file(s) inside our repository folder. Then we head back to the Terminal, make sure we cd into our repository folder if we’re not already there.

Then we add and then commit our changes.

git add fileWeChanged

If we have multiple files we’ve changed:

git add file1 file2

Now let’s commit them.

git commit -m 'fixed our header'

This is the commit message so we know what we changed in this version of our code.

We continue this process in a loop. We work in our IDE. We save. When we are ready we return to the Terminal, add our files, then commit them with a message.

To see all your commits

git log

OR

git log --pretty=oneline

A GUI for working with Git instead of the Terminal

There is a GUI/Graphical Interface should you prefer to use one.

In general, there are more options when working in the command line.

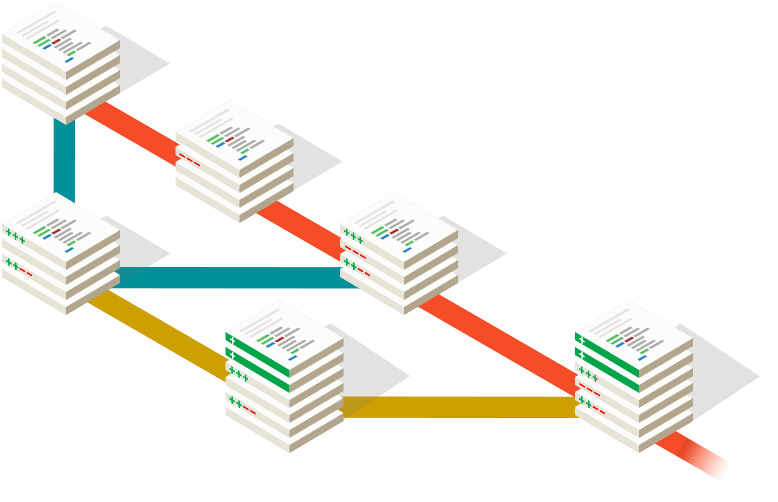

Branching

You may wish to work on several copies of your project with slightly (or dramatically) different codebases. Maybe you have a desktop and a mobile version of your project, or one for Mac and PC, or regular and experimental versions.

For each version you can create a different branch.

git checkout -b version2

Find out which branch you’re in

git branch

Merging Branches

Maybe you were working on a stable branch and an experimental branch and you want to merge these two together. Generally, your first and main branch is called the master branch. You can merge your version2 with your master.

git merge version2

GitHub versus Git

Git is the software you use on your local computer to track your repository’s files. You can always work in Git and not use GitHub if you just want to track your changes locally. However, if you want to make backup copies stored on a remote server, or work collaboratively on code with others, you’ll want to put your code online. GitHub is a great way to do that and it works seamlessly with Git.

Let’s make our local repository for a project

mkdir hello-github

cd hello-github

git init

We’ve made a project folder. Moved inside it. And initialized it so that Git will be used for tracking our files over time.

Adding a remote GitHub repository

We want our remote GitHub repository to be a copy of the important commits (aka snapshots of our project’s complete code files).

Let’s connect our local repository to a GitHub repository.

On github.com let’s create a repository. Click the + button. Give the project a name. Initialize it. It will give you a git URL. Copy it.

Now go back to your Terminal. To connect our local repository to the one hosted on GitHub, we run:

git remote add origin git://github.com/github-name/project-name

Pushing our code to our Github repository

After you’ve connected your local repository to the GitHub one we need to run this command for the first time.

git push -u origin master

Going forward our standard protocol will be to just run

git push

This takes our committed files and pushes a copy to our GitHub repository.

READMEs

It is considered good form to make a README.md file in Markdown text and saved in the root directory of your repository. This can contain basic info on the project, starter information, or anything else. GitHub will automatically present this file when someone visits your repository’s page.

Edit the ReadMe file (example)

git add README.md

git commit -m 'added README.md'

git push origin master